The following is a post that was put up on The Amish Catholic by Rick Yoder. He graciously gave me permission to repost it. If you want to see the original post just click HERE.

From the Amish Catholic…

I’ve taken a major interest in Scotus recently. His Christology and Mariology seem to be treasures that remain largely unexploited by contemporary theologians, in part because he was recognized as being in the right about a doctrine that became dogma almost two hundred years ago. He is at the center of ongoing debates about the advent of secularism and modernity, debates which I am not competent to comment on at this time. Nevertheless, I thought it might be fun to examine some of the ways that Catholics (mostly Franciscans) have memorialized him in art over the course of the last several centuries. In some sense, the variety of depictions here tell a story of a lineage long overshadowed by other, more influential streams of thought. Thomism in particular has had a near perennial appeal within the Church, whereas Scotism, it seems, has largely been a niche concern. After all, Scotus has not yet been canonized or joined the ranks of the Doctors of the Church. This inequity arose from a variety of factors. No doubt, the fate of Scotism has come partially from Scotus’s own difficult style and vast intelligence. There’s a reason he’s called the “Subtle Doctor.”

May my small collection here help rectify that oversight on this, his feast day. [This was originally posted on Nov. 8th, 2017 – the Feast of Bl. John Duns Scotus]

John the Scot (c. 1266 – 8 Nov. 1308), appearing in what must be one of his earliest depictions: an illuminated capital. (Source)

A Renaissance portrait of the Blessed John Duns Scotus. One point that people forget about Scotus is that he defended the rights of the Church against Philip IV, who had wanted to tax church properties. For his bold stance, he was exiled for a few years from Paris. (Source)

Perhaps the most famous, a late-Medeival, early-Renaissance portrait of Scotus. The name of the artist escapes me. (Source)

An early modern engraving of Scotus, probably early to mid 15th century. (Source)

Here he is with St. Albert the Great, one of the Dominican Doctors. (Source)

Scotus the Scholar. Age and provenance unclear; my guess is late 17th century, though it may be later. (Source)

Scotus receiving a vision of the Christ Child, 17th or 18th century. Although chiefly remembered for his metaphysics and Mariology, Scotus made major contributions to Christology, defending the Patristic idea of Christ’s Absolute Primacy. (Source)

From the early modern period, it became typical to depict Scotus with representations of the Virgin Mary, whose Immaculate Conception he famously defended. This piece, probably from the 18th century, is one such example. It also contains a pretty clear criticism of Aquinas – Scotus looks away from the Summa to gaze lovingly at Mary (Source: this very friendly take on Scotus by a prominent popular Thomist)

A slightly more dramatic iteration of the same theme. Scotus is inspired by the Immaculate Conception. (Source)

My single favorite image of Scotus is this ludicrously over-the-top Rococo depiction of Scotus and the Immaculate Conception triumphing over heresy and sin. He holds the arms (no pun intended) of the Franciscan order. His defense of the Immaculate Conception surpassed the doubts of even his own order’s great luminary, St. Bonaventure. And what a marvellously simple argument it was, too. Remember: POTVIT DECVIT ERGO FECIT. (Source).

Likewise, this totally marvelous Colonial Mexican painting from the Franciscan monastery of Izamal, Yucatan, is something else. Rare is the saint granted wings in traditional iconography, though the trend was not uncommon in early modern Mexican art (Source)

The mystery solved! This version by Johannes Pitseus comes from 1619, and served as a model for the Izamal piece. Here, it’s clearer that the heads represent various heretics, including Pelagius, Arius, and Calvin. (Source)

This ceiling relief from Landa, Querétaro, uses the same iconographic lexicon. It seems that the Franciscans of colonial Mexico had a set of stock images to propagate devotion to their own saints. (Source)

Here’s another unusual image of Scotus. In this mural of Mary Immaculate, or La Purísima, we see Scotus alongside St. Thomas Aquinas…and wearing a biretta! A remarkable addition, unique among all other depictions of the Subtle Doctor that I know of. (Source)

Moving away from Mexico, we come to this rather uninteresting French portrait of Scotus. Not all 18th century portraits of the man are elaborate bits of Franciscan propaganda. (Source)

A late 18th or early 19th century depiction of Bl. John Duns Scotus. If this is in fact an English painting, its creation at a time of high and dry Anglican Protestantism poses interesting questions about the use of Scotus as a figure of national pride. (Source)

I’m unsure of how old this image is; my guess, however, is that it represents a 19th century imitation of late Medieval and Renaissance style. (Source)

A great 19th century painting of the Immaculate Conception by Danish Franciscan Albert Küchler. Scotus, who is on the bottom right, is here depicted alongside other Franciscan saints – S.s. Francis of Assisi, Anthony of Padua, and Bonaventure. (Source)

This looks like a Harry Clarke window, though it may just resemble his style. In anyway, we see here Scotus holding a scroll with his famous argument for the Immaculate Conception epitomized – “He could do it, It was fitting He should do it, so He did it.” (Source)

John Duns Scotus, once again contemplating the Immaculate Virgin and offering his mighty works to her. (Source)

Another stained glass window, this time indubitably from the 20th century. We see here Scotus worshiping the Christ Child and his Immaculate Mother. (Source)

Scotus depicted in on the door of a Cologne Cathedral, 1948. He represents the supernatural gift of Understanding. (Source)

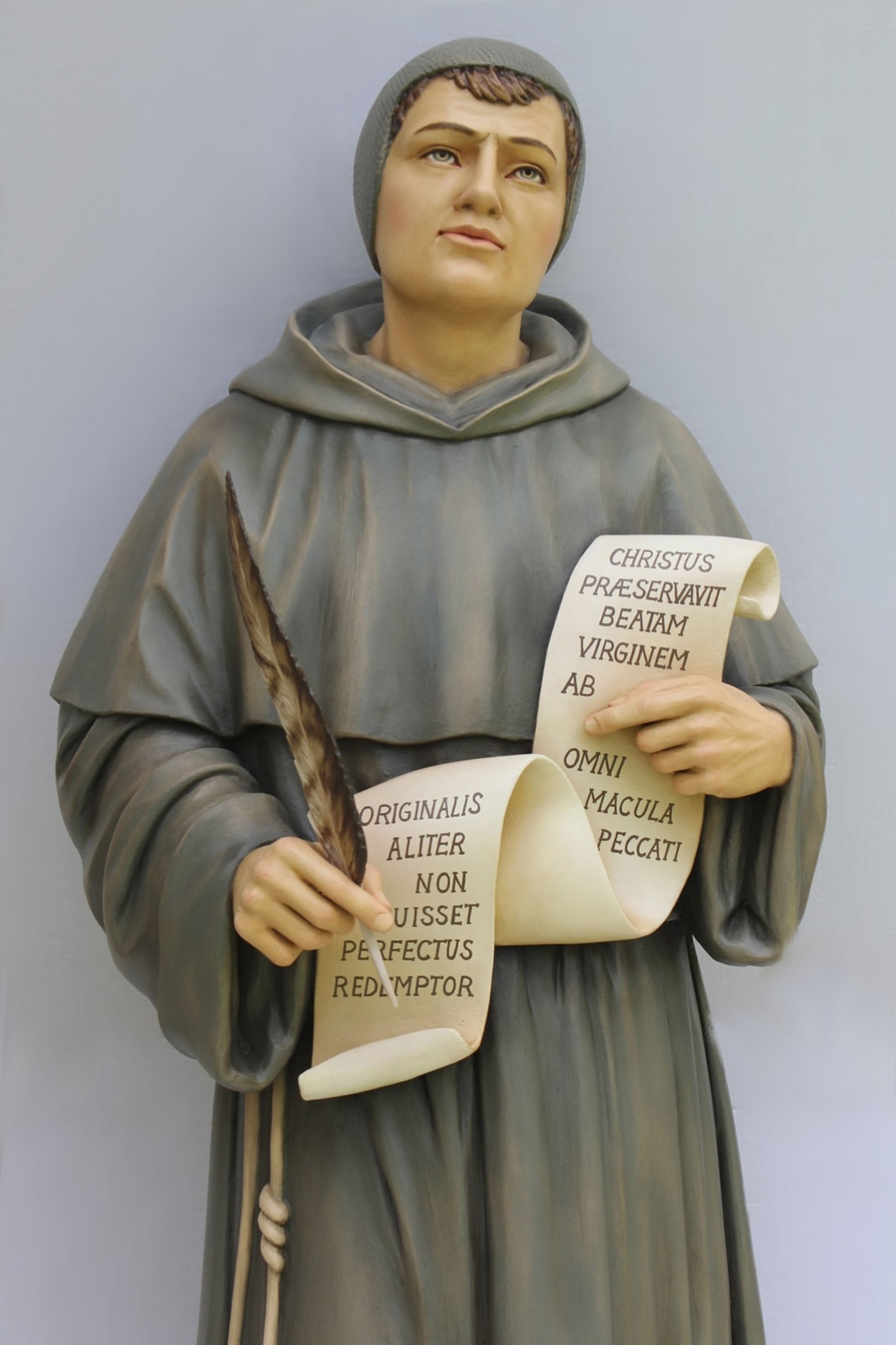

A contemporary statue of Scotus. (Source)

Scotus with a modification of the Benedictine phrase. “Pray and Think. Think and Pray.” Not a bad motto. (Source)

A 20th or 21st century image of the Blessed Scotus (Source).