Cristo, il Principio del creato – II parte

P. Maximilian M. Dean, FI

In principio Dio creò

Non è per caso che Giovanni vuole iniziare il suo Vangelo con le stesse parole che danno inizio a tutta la Sacra Scrittura. Infatti “sul rotolo del Libro” (Salmo 39,8) è scritto: “In principio Dio creò il cielo e la terra” (Gn 1,1), e così “l’alfa” di tutta la rivelazione divina è proprio questo in principio. Ma Giovanni, essendo l’ultimo scrittore della Bibbia, dà “l’omega” alla rivelazione, cioè “in principio era il Verbo…” (Gv 1,1). “L’alfa e l’omega”, dunque, di tutta la rivelazione di Dio non è altro che in principio Dio creò e in principio era il Verbo. Mentre tutti riconoscono subito il riferimento espresso di Giovanni alla Genesi, non tutti poi interpretano in principio dei due brani nello stesso modo.

Abbiamo visto come Cirillo, Agostino e Bonaventura nei loro commenti al Prologo interpretarono l’in principio di Giovanni come nel Padre, per dire che il Verbo era eternamente ed essenzialmente nel Padre che è il principio per antonomasia. Però, quando leggiamo la prima riga della Genesi risulta evidente che in principio non può riferire al Padre. Difatti, il dire “nel Padre Dio creò il cielo e la terra” non ha nessun senso. Perciò deve essere altrettanto per il Prologo di Giovanni, altrimenti si rompe il vincolo stretto e esplicito inteso dall’Evangelista fra il suo Vangelo e la creazione dell’universo.

Il legame è espresso in tutti i modi perché non soltanto inizia con le stesse parole, e non soltanto parla di “luce” e “tenebre”, ma anche elenca sette giorni. Il primo giorno c’è il Verbo che si fece carne (1,1-14) e la testimonianza di Giovanni Battista (1,6-8.15.19ff). Poi, sottilmente, l’Evangelista dice “il giorno dopo” (1,29), “il giorno dopo” (1,35), “il giorno dopo” (1,43), e poi “tre giorni dopo” (2,1) per arrivare al settimo giorno con le nozze di Cana.

Parliamo, quindi, di una nuova creazione, d’acqua cambiata in vino per così dire, dove quello che conta è “l’essere nuova creatura” (Ga 6,15) e Gesù proclama: “Ecco, Io faccio nuove tutte le cose” (Apoc 21,5). Per noi la Sua venuta è una nuova creazione; invece per Dio è la piena realizzazione del Suo disegno originale da Creatore che volle, e vuole ancora, che tutto si ricapitoli in Cristo (cf. Col 1,18.20). Per noi, per così dire, è l’acqua cambiata in vino; mentre per Dio è il compimento del Suo piano già previsto prima dei secoli: aveva sempre voluto “il vino buono”, ma l’aveva conservato “fino ad ora”.

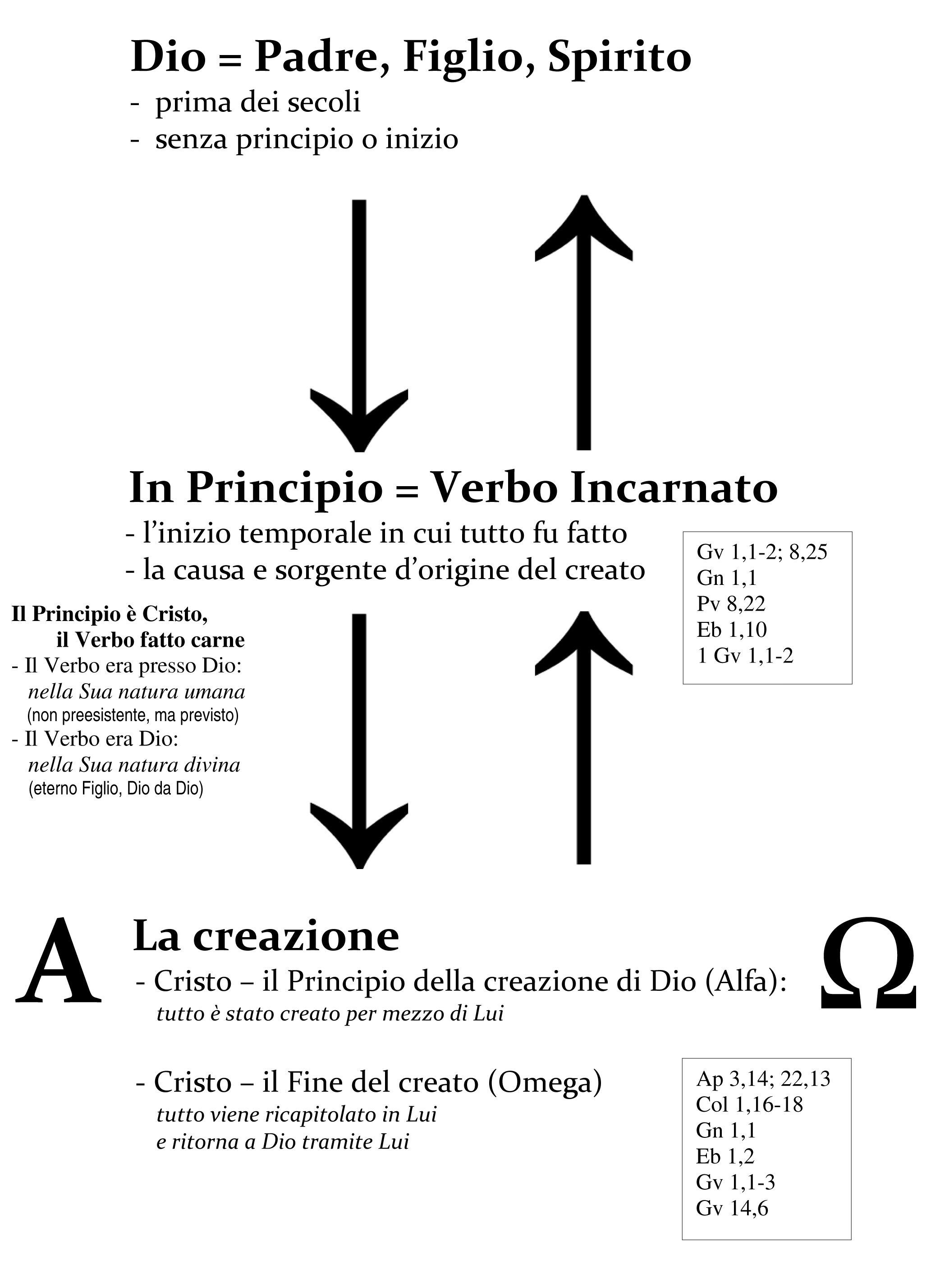

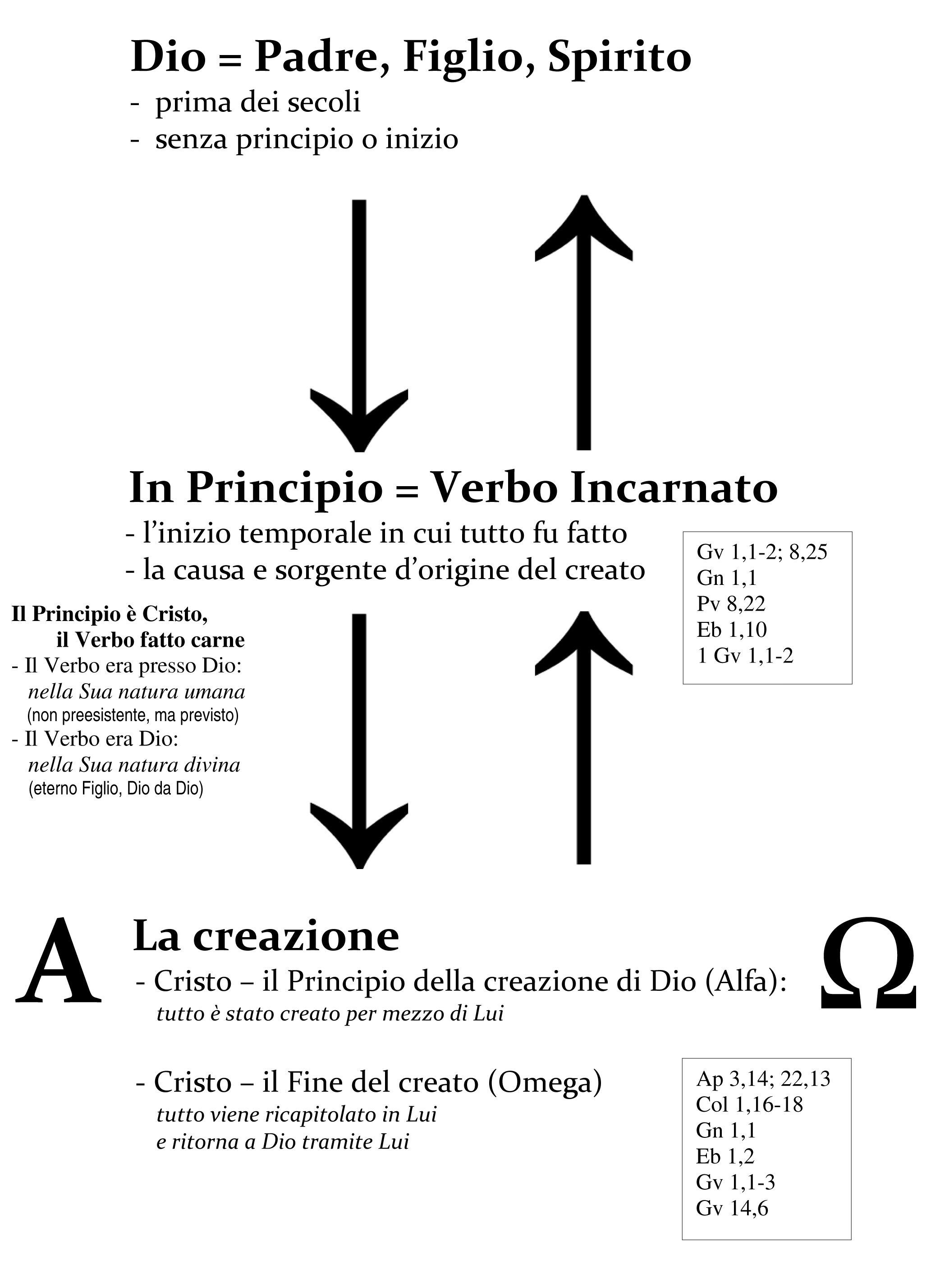

Dobbiamo stabilire che dalla prima riga della Genesi in poi l’espressione “in principio” nella Sacra Scrittura si riferisce alla creazione. Ne segue che “in principio era il Verbo” non intende il fatto che il Verbo eterno era nel Padre, ma ben altro, cioè che il Verbo Incarnato era il principio in cui tutte le cose furono create.

E comunque, non potrebbe essere altrimenti, perché la parola principio, legata al contesto e al significato della Genesi – “In principio Dio creò” – parla non soltanto di una sorgente d’origine, ma anche d’un inizio temporale. Né il Padre eterno, né il Verbo eterno, né lo Spirito eterno, ossia l’eterno Dio Trino ed Uno, nessuno di Loro può avere un inizio, un principio come il creato. Ogni Persona divina, come Dio, è senza inizio, senza principio per definizione e, come vedremo, la Chiesa non si stanca mai di confessare e insegnare che Dio per natura – sia il Padre, sia il Figlio, sia il Santo Spirito – è prima di ogni secolo, prima e fuori del tempo, ossia eterno. La creazione, invece, ha un inizio ben preciso: “In principio Dio creò”.

Fissiamo lo sguardo sull’insegnamento solenne della Chiesa su questo punto per comprendere meglio che in principio non può riferirsi alla Divinità in Sé – né a Dio Padre né al Verbo in Sé. Dato che prima della creazione non ci fu tempo, ma solo l’eterno Dio, è chiaro che Lui è “prima di ogni creatura”[1]. Perciò i Simboli, Concili e Papi della Chiesa, quando parlano di Dio Trino ed Uno – sia della Divinità in Sé che delle Tre Persone divine (e del Figlio in modo particolare) – mai parlano di un principio[2]. Anzi ripetono quasi ad infinitum che Dio è senza principio e prima di ogni secolo. Ecco alcuni esempi fra tanti che parlano in particolare della Divinità del Figlio, ma si riferiscono pure al Padre e allo Spirito:

– Il Papa S. Leone Magno nel 449 spiega che la natura divina di Cristo viene “dal Padre prima di ogni principio”[3], per dire che quando parliamo del Verbo in Sé, come Dio, non è in principio, ma prima di qualsiasi principio.

– Il Papa Anastasio II nel 497 afferma che l’unigenito Figlio, “nato dal Padre secondo la Divinità”, è “prima di ogni secolo, senza principio”[4]. Non in principio, dunque, ma senza principio.

– Il Papa S. Ormisda nel 521: “Il Figlio era prima del tempo”[5]. Così il Verbo in Sé, come Dio, è prima del tempo, prima del principio, prima di ogni secolo; mentre il Verbo fatto carne è nel tempo, in principio, in questi giorni pur rimanendo Dio eterno. Vuol dire che se Giovanni avesse voluto parlare del Verbo in Sé nel Prologo e non del Verbo umanato, avrebbe dovuto scrivere: Prima dei secoli era il Verbo. Invece scrisse: “In principio era il Verbo”. Approfondiremo questo nelle prossime pagine.

– Il Concilio di Costantinopoli nel 553 dichiara nel suo Canone 2: “Se qualcuno non confessa che il Dio-Verbo aveva due nascite, l’una cioè incorporale, fuori del tempo, prima dei secoli dal Padre, l’altra veramente negli ultimi giorni di Colui che discese dal cielo e fu incarnato dalla santa, gloriosa e sempre Vergine Maria, Madre di Dio, nato da essa, questi sia anatema”[6]. La Chiesa non parla mai della Divinità di Cristo in termini di tempo, mentre la Sua umanità sacra viene sempre descritta nel tempo.

– Il Concilio di Toledo VI nel 638 esprime che il Figlio viene dal Padre “al di fuori del tempo, prima di ogni creatura, senza inizio, nato e non creato”[7]. È chiaro, quindi, che nel parlare della Divinità e delle Persone divine, la Chiesa non parla di tempo o d’un inizio perché Dio è eterno.

San Cirillo dice schiettamente: “Parlando dell’Unigenito non è possibile, d’altronde, pensare a un principio nel tempo. Giacché è prima di ogni tempo, ed esiste prima dei secoli… Ma poiché il Figlio è più antico dei secoli, non potrà essere stato generato nel tempo, ma Egli era sempre nel Padre come da una sorgente…”[8]. Difatti nella Genesi, così pure nel Vangelo di Giovanni, in principio indica l’inizio del tempo, l’inizio della creazione, e Dio – Padre, Figlio e Spirito Santo – è ben fuori del tempo, increato, senza inizio e senza fine, eterno.

In principio, dunque, non può essere applicato al Figlio in Se stesso come Dio, come pure al Padre e allo Spirito Santo, se non solo per via d’accomodazione, ossia usando il termine principio come un modo di dire (i.e. il Padre è il “principio” della Trinità, ossia la sorgente eterna da cui il Figlio procede eternamente, ma si deve sempre aggiungere che è il principio senza principio[9] e alla fin fine abbiamo un’accomodazione molto limitata e che non si sincronizza, come vedremo, con il resto della Sacra Scrittura).

Però, in Cristo, il Verbo fatto carne, c’è una natura creata unita a quella divina nella Persona del Verbo e il Cristo ha il Suo inizio nella “pienezza del tempo” (Ga 4,4). Ed ecco la chiave per capire che cosa vuol dire “in principio Dio creò” e “in principio era il Verbo”. In tutti e due i brani, come vedremo con tanta chiarezza, stiamo parlando del Verbo Incarnato, principio della creazione[10].

Sì, si può applicare l’espressione in principio a Dio senza accomodazione solamente in quanto “Figlio dell’uomo”, in quanto incarnato, e ciò vale soltanto per Cristo perché né il Padre né lo Spirito assunsero la carne dalla Vergine, ma unicamente il Figlio. Perciò, quando l’Evangelista dice: “In principio era il Verbo”, bisogna capire che sta parlando del Verbo umanato: Cristo era il Principio.

Inoltre, non si può applicare l’espressione in principio al Verbo eterno senza riferimento all’Incarnazione perché, come dice san Cirillo del Verbo eterno: “Il Figlio, infatti, è prima dei secoli, ed Egli stesso è Creatore dei secoli; né può, in alcun modo, essere limitato dal tempo Colui che ha la generazione più antica del tempo”[11].

Inoltre, occorre esaminare la funzione del verbo essere nella frase “in principio era il Verbo”. La funzione potrebbe essere compresa in due modi. Primo, come predicato aggettivo, dove in principio viene applicato al Verbo in senso dell’inizio della creazione. Vale a dire che quando Dio creò l’universo aveva davanti il decreto dell’Incarnazione, vedeva Gesù, e allora il principio del creato e dunque del tempo era il Verbo Incarnato: senza di Lui infatti niente fu creato e il tempo non aveva suo inizio. Secondo, come predicato nominativo dove essere vuol dire essere uguale a. In questo caso il Verbo Incarnato era il principio creante in cui tutto fu fatto, non soltanto in senso temporale, ma come sorgente d’origine, come causa. Insomma, prendendo cenno da tutte e due le funzioni, si può ben dire che Cristo fu sia l’inizio temporale, sia la sorgente d’origine della creazione.

Di più, con questa interpretazione il Prologo diventa più consistente: Dio si riferisce alla Divinità (non qualche volta alla Divinità, qualche volta al Padre); il Verbo si riferisce sempre a Gesù Cristo quale Figlio di Dio e Figlio di Maria (non qualche volta al Verbo increato nel Padre senza riferimento all’Incarnazione, qualche volta al Verbo fatto carne).

Continua…

[1] Il Figlio, con il Padre e lo Spirito, è ante omnem creaturam (cfr. Denz. 490, ecc.).

[2] Ante saecula, ante omnia saecula (cfr. Denz. 76, 301, 357, 617, ecc.), ante tempora (Denz. 368), sine tempore (Denz. 422), intemporaliter (cfr. Denz. 490, 617, ecc.).

[3] Ex Patre ante omne principium (Denz. 297).

[4]Ante omnia quidem saecula sine principio (Denz. 357; cfr. 76, ecc.).

[5] Qui ante tempora erat Filius (Denz. 368).

[6] Ante saecula, sine tempore (Denz. 422). Basta vedere il Concili di Chalcedon e Costantinopoli I per capire che l’insegnamento che il Verbo in Sé come ante saecula è dogma solennemente proclamato (Denz. 150 e 503-504).

[7] Intemporaliter ante omnem creaturam sine initio (Denz. 490; cfr. 617).

[8] Cirillo, op. cit. I, I (p.38).

[9] Cfr. ibid. I, 1 (p.40) e Agostino, Contra Maximin., II, c.17, n.4; PL 42, 784.

[10] Cfr. P. Ruggero Rosini, Il Cristo nella Bibbia, nei Santi Padri, nel Vaticano II, pp. 109-119, dove si tratta di Cristo come il Principio.

[11] Ibid. I, III (p.58).